Modernizing Transit in Monmouth County

Unlocking the Potential of the North Jersey Coast's Existing Infrastructure

August 23, 2022

Overview

Travelers at the Aberdeen–Matawan station on the North Jersey Coast Line [*1].

Home to some 640,000 people, Monmouth County, New Jersey is the fifth most populated county in the state and makes up a notable portion of the New York Metropolitan Area west of the Hudson River. The county contains the northernmost part of the popular Jersey Shore, which starts only 18 miles south of the tip of Manhattan. As such, Monmouth has long been a popular destination for commuters and recreation seekers alike. However, although the county is deeply tied into the most transit-friendly metropolis in the United States, much of its current transit infrastructure is not being used up to its potential. While New Jersey Transit does offer rush hour-focused express bus service into Manhattan and North Jersey Coast Line (frequently abbreviated to the Coast Line) commuter rail service, options are far more limited for off-peak travel or for intermediate trips within the county. Local bus service does little to help matters: it is sparse and infrequent, with significant portions duplicating rail service.

The inefficient utilization of infrastructure is most notable along its Atlantic shore. These coastal communities are some of the densest and most walkable parts of the entire county. With some census tracts exceeding 10,000 people per square mile, these are exactly the kind of places that transit can serve well. However, there is a problem: the electrified portion of the North Jersey Coast Line—which travels through the heart of these communities—ends at Long Branch, right where the line reaches the ocean. As a result, travel between some of the densest parts of Monmouth County and points north requires a transfer between electric trains and slower, more polluting diesel-powered trains.

Monmouth County’s densest communities lie along the route of the North Jersey Coast Line, especially the outer portion that lacks electrification and receives limited service.

The Effective Transit Alliance believes that a modernization of Monmouth’s transit service, according to global best practices, would unlock significant ridership boosts for a very modest investment. Our proposal would deliver hourly or better electric rail service along the entire 66-mile Coast Line to New York Penn Station, speeding service while eliminating transfers and local diesel emissions. All stations would have accessible, comfortable level boarding, and local bus service would be redesigned to run at usable frequencies in a manner that complements and feeds the rail line. While these improvements will require an upfront capital investment, the cost would pale in comparison to the sums that the NJ Turnpike Authority is currently proposing to spend on highway expansions.

Better still, we believe that modernization of the North Jersey Coast Line could serve as a template for similar incremental transit improvements across Greater New York. Compared to other outlying regional rail lines, this project is within relatively easy reach, with only 15 route-miles of track needing overhead electrification. What’s more, existing diesel shuttle trips can be straightforwardly consolidated with existing electric train service, allowing direct service without new train capacity under the Hudson River. This modernization project would help New Jersey Transit and its partners build up the institutional muscle memory it will need to complete more complex upgrades. Executed well, the modernization of transit in Monmouth County could serve as a template for similar upgrades to the rest of Greater New York’s regional rail system, not only benefiting riders, but paving the way for better regional service as the Gateway Project comes online.

Bringing the North Jersey Coast Line into the Twenty-First Century

Modern transit systems run frequent, all-day service to serve a full range of trips, not just peak commutes, with buses and trains running in an integrated manner that encourages transfers. Currently, the outer North Jersey Coast Line gets diesel service between Bay Head and Long Branch running anywhere between 30 minutes and 2 hours apart. Of these trips, only three inbound and three outbound trains per weekday run between Bay Head and New York using electro-diesel dual mode equipment, and the rest are shuttles forcing a change at Long Branch. The shortest scheduled Long Branch–Bay Head travel time is 40 minutes. Pre-pandemic, this portion of the line attracted almost 3,000 daily boardings. Our plan would significantly improve the rail service’s attractiveness for both short trips and long ones between the Shore and points north.

ETA’s plan would extend overhead electrification over the entire North Jersey Coast Line and replace low-level platforms like these at Little Silver with high ones that are level with train car floors.

Our modernization plan consists of hourly service—all day, every day—and capital projects to speed trip times. First, it would add missing diesel shuttle trips so that the entire line receives at least one train per hour all day. Second, we propose to complete overhead electrification to Bay Head and eliminate the Long Branch transfer, affording fully one-seat New York–Bay Head service. Finally, to be done concurrently with electrification if possible, we propose to convert all remaining Coast Line stations to high platforms with step-free access in order to hasten boarding and alighting.

Potential funding sources

Judging from other recent US projects, the required capital construction can be expected to cost around $300 million. This cost is a small fraction of the $1.35 billion-proposed Garden State Parkway widening in Monmouth County, let alone the rest of the expansions in the New Jersey Turnpike Authority’s latest capital plan. The New York area has historically funded many transit improvements using highway toll proceeds, and the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) recently published guidance on expanding this practice to transportation formula funds. Moreover, USDOT recently announced a $1.75 billion grant program for station accessibility projects.

Monmouth County local buses

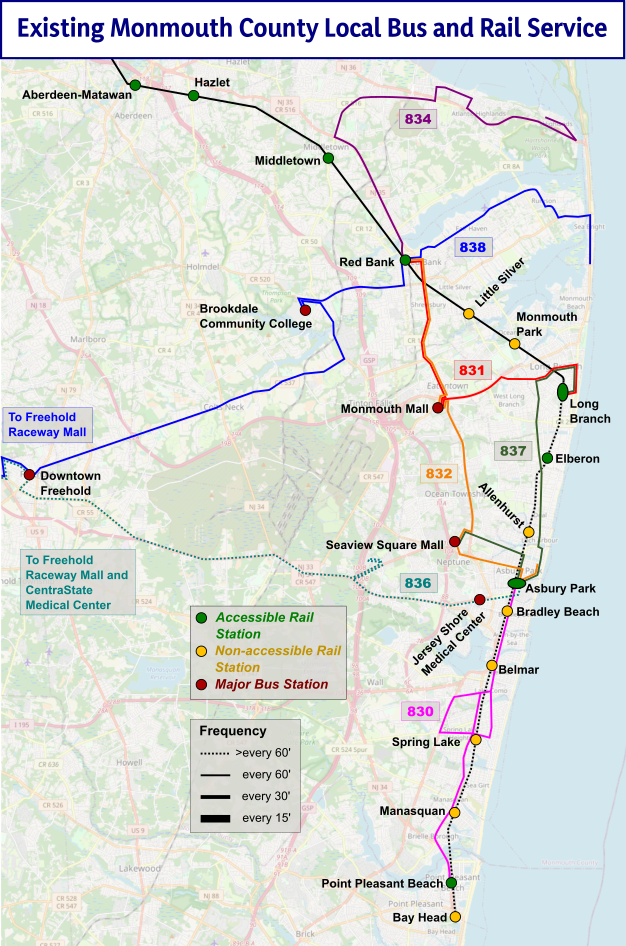

In general, high-quality bus service runs frequent service on legible, direct routes. Today, seven bus routes—the 830, 831, 832, 834, 836, 837, and 838—run intra-Monmouth County service under a contract with Transdev worth $22.2 million over 3 years. None of these routes run more than once hourly, and most offer no evening or Sunday service. Simply put, the service is too sparse to be very useful. Moreover, many of the routes contain jogs that increase trip times and segments that parallel rail lines. As a result, pre-pandemic, the intra-Monmouth bus network attracted about 4,000 daily boardings in a region with hundreds of thousands of residents.

Our bus proposal would offer the densest parts of Monmouth County a usable baseline service for a minimal operating cost increase. In brief, as a starting point, every Monmouth County local bus would run for 18 hours a day, seven days a week, with buses arriving at least every 30 minutes. We believe that reasonably frequent bus service on a few routes will build political will for further service increases better than spreading buses thinly around a large area.

Table 1: Current vs. future trip times

| Station | Today | Add overhead wire | Add high platforms | Convert to EMU trains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Branch | 0:00 | 0:00 | 0:00 | 0:00 |

| Elberon | 0:04 | 0:04 | 0:04 | 0:03 |

| Allenhurst | 0:08 | 0:08 | 0:08 | 0:06 |

| Asbury Park | 0:12 | 0:11 | 0:11 | 0:09 |

| Bradley Beach | 0:15 | 0:15 | 0:13 | 0:11 |

| Belmar | 0:19 | 0:19 | 0:17 | 0:14 |

| Spring Lake | 0:23 | 0:23 | 0:21 | 0:17 |

| Manasquan | 0:27 | 0:27 | 0:25 | 0:20 |

| Point Pleasant Beach | 0:32 | 0:34 | 0:31 | 0:24 |

| Bay Head | 0:40 | 0:37 | 0:34 | 0:26 |

ETA’s plan would improve bus service in Monmouth County [*2].

Rail trip time

The combination of level boarding and electric traction would substantially reduce rail trip times (Table 1). The fastest scheduled Long Branch-Bay Head trip—which we used as our baseline—is 40 minutes. We estimate that the improved acceleration of a dual-mode set operating in electric mode would cut the trip to 37 minutes. We assume that high platforms would reduce dwells by 30 seconds per station; this would further shave the Long Branch–Bay Head trip time to 34 minutes and save 30 seconds at Little Silver. With electric multiple unit (EMU) trains, modeling shows that trip time could be cut to just 26 minutes, a 40% reduction from today. Note that the current schedule, which is listed in the “Today” column, places all the padding between the penultimate and last stop, while our schedule modeling distributes it evenly throughout.

Costs and Benefits

Capital costs

In the 1990s, Amtrak electrified 155 double-track route miles from New Haven to Boston for around $6.8 million per mile in 2022 dollars. The contractor substantially completed the project in summer 2000 about four years after beginning work. At this construction cost, which is quite high by global standards, completing electrification on the Coast Line would cost around $100 million. Since the North Jersey Coast Line already has a conflict-free connection to the Northeast Corridor and existing service to Penn Station, completion of wire to the line’s end allows straightforward consolidation of the shuttle trips into one-seat New York–Bay Head runs. We anticipate that NJ Transit’s existing rail fleet suffices for the service increase proposed herein. Most of the shuttle sets already use electro-diesel dual mode locomotives, and more of them have been ordered to replace aging diesel-only locomotives.

Recent high-platform projects, such as the recently completed Chelsea, MA, station, have cost around $25,000 per linear foot of platform. Seven full-time stations on the line currently lack high platforms; equipping all of these stations with two side platforms each long enough for a six-car set would likely cost around $200 million. We recommend closing Monmouth Park, which is a summer-only stop that lacks nearby trip generators.

This proposal deliberately assumes recent U.S. construction costs. Research has confirmed that the United States pays uniquely high prices for its transit infrastructure. In most other industrialized countries, the construction required for this proposal would cost $100 million or less. Investigation into the problem’s root causes has found that informed, empowered internal design staff and a culture that prioritizes speed and standardization play major roles in construction cost control. The state of New Jersey and the federal government should be actively seeking opportunities to imitate these practices so that transit funds reach as far as possible.

The MBTA’s Chelsea station demonstrates that constructing high platforms need not be cost prohibitive [*3]

Table 2: Estimated costs and ticket revenue of phased North Jersey Coast Line service improvements

Bus operating costs

We estimate the cost of our bus proposal using the current contract cost and estimating the current level of service hours from schedules. Using these sources, we calculate that our proposal would cost around $6.3 million more yearly. Widely accepted ridership modeling practices predict that added ticket revenue would offset much of this cost. This service level would likely require a few more buses at Transdev’s Neptune garage, which handles 20 today. We expect the garage to need minimal modification, but actual needs warrant further investigation. Pre-pandemic, moving one passenger one mile cost NJ Transit $0.58 on a commuter train versus $1.07 on a bus, so it is to the agency’s advantage to have buses complement the Coast Line rather than duplicate it.

We propose to reroute buses onto more direct routes where the train does not run. Once the whole Coast Line runs at least hourly all day, the entire 830 route and the 837 north of Asbury Park can be eliminated. In our proposal, the 837 would now run from Seaview Square via Sunset Avenue to Asbury Park station. The 831 would now run from the Monmouth Mall along NJ-36 and Broadway to Long Branch Station. The 832 would now start at Red Bank Station and continue down NJ-35 past Seaview Square along Neptune Boulevard to reach Jersey Shore Medical Center before using Corlies Avenue to reach Asbury Park. The 834 would use Linden Avenue to reach NJ-36 from Highlands and no longer detour into Leonardo. Moreover, it would terminate at Middletown instead of Red Bank station.

| Scenario (amounts may not add due to rounding) | Today | Hourly diesel shuttles | Hourly electric service to New York + Full accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily trains (assuming six cars each) | 34 weekday 22 weekend |

48 weekday 40 weekend |

48 weekday 40 weekend |

| Marginal operating expenses (millions/year) | $0 | ($9.9) | ($5.6) |

| Marginal passenger revenue (millions/year) | $0 | $1.3 | $3.2 |

| Marginal net cost (millions/year) | $0 | ($8.6) | ($2.5) |

ETA’s plan would eliminate engine switching at Long Branch station [*4].

Rail operating costs

Our modeling estimates that year-round hourly diesel shuttles would cost $9.9 million per year and stimulate $1.3 million in additional ticket revenue for a total net cost of $8.6 million annually (Table 2). We assume that added diesel service would cost NJ Transit’s systemwide average unit cost of $20 per car mile. Our proposal would add 7 more weekday and 9 more weekend round trips of 30 miles each, times six cars. This method likely overestimates the net cost. Rail systems carry substantial fixed costs, which means unit costs decrease as service is added, and NJ Transit already runs hourly shuttle service most of the day on summer weekends.

With platforms and wire, we anticipate the annual operating cost of the proposed service level to be slightly over the total cost incurred today. We use the New York City Subway’s cost of $17 per car mile to approximate that of electric service between Long Branch and Bay Head. Since that system is fully electrified with fully level boarding and runs a reasonable complement of midday service with considerable increases during the morning and evening peaks, we believe this is a reasonable choice. On balance, electric trains save money over diesel ones since they are lighter, faster, and contain fewer moving parts to maintain, even after accounting for overhead wire maintenance.

Of note, the Chicago ‘L’ incurs a cost of around $10 per car mile, or $14 if scaled to New York wages. That system runs service 24/7 in a less peaked fashion than is seen in New York and also seems to perform system maintenance more efficiently. There is good reason to believe that gradual evolution of practices on New York’s commuter rail network to all-day electric regional rail would bring operating expenses closer to those of the L. Electric multiple units that do not have low-level boarding stairs cost substantially less to acquire, maintain, and staff than NJ Transit’s current equipment.

Continued diesel operation on the outer North Jersey Coast Line is highly suboptimal. Because the line has especially close stops, overhead electric propulsion unlocks large trip time cuts over diesel. Moreover, reliable implementation of a full New York-Bay Head one-seat ride with diesel past Long Branch would require reinstallation of a recently removed fueling facility at Bay Head. For similar reasons, we do not recommend battery trains, which generally ply secondary routes away from major cities, for the Coast Line. Battery trains—of which NJ Transit has none—cost more to acquire and accelerate more slowly than comparable overhead wire trains, which would lengthen trip times, decrease reliability, and force greater spacing between trains on the congested railroad near New York Penn Station. Moreover, without full overhead wire to Bay Head, crews would still have to perform and verify a mode changeover at Long Branch, adding to the station dwell time.

Additional Improvements

Further Rail Speedups

Concomitant with our proposal for the outer North Jersey Coast Line, we urge NJ Transit and Amtrak to examine the rest of the route for potential speedups. Increasing speed reduces the crew time necessary to carry passengers to their destinations and improves the service’s attractiveness. NJ Transit can model their efforts on the recent NYC Transit Save Safe Seconds initiative, which identifies existing trackage that could safely allow speeds higher than the current limits. The new Raritan River drawbridge is to have a design speed of 60 mi/h, versus 35 mi/h today, and the new high platforms at Perth Amboy station will cut significant dwell time. Today, Coast Line trains are limited to 30 mi/h when entering and leaving the Northeast Corridor even though every switch is good for 45 mi/h. Trains can likely traverse curves, such as at Matawan (currently signed for 45 mi/h), Red Bank (60 mi/h), and Long Branch (25 mi/h), at higher speeds than today’s posted limits.

Other buses

In tandem with our bus proposal, NJ Transit should be seeking opportunities to consolidate bus service and improve frequency around Central Jersey. For example, with hourly Coast Line service, the 317 could turn back at Point Pleasant Beach Station rather than continuing to Asbury Park along the railroad tracks. It is key to note that the NJ-35 corridor, while parallel to the Coast Line in a macroscopic sense, has a dense concentration of residents and jobs in its own right and merits its own local bus service. In a future phase, NJ Transit should consider a route linking Keansburg, which is one of the county’s most densely populated and economically disadvantaged municipalities, with either Red Bank or Brookdale Community College.

Farther north, there are opportunities to use Coast Line stations as bus transfer hubs. The 817 bus, which currently runs hourly meandering through the Bayshore area and paralleling the Coast Line from Cliffwood Beach to Perth Amboy, could connect the NJ-36 corridor to Aberdeen–Matawan station at much higher frequency. Moreover, the 130, 131, 132, 133, 135, 136, and 137 express bus services to New York converge in the same area. Many of these routes are peak-focused or peak-only. Redirecting the routes to Aberdeen–Matawan or South Amboy would allow the buses to run frequently all day along US-9, NJ-79, and other major roads serving intra-county traffic as well as onward connections. Similarly, the 115 and 116 express buses linking eastern Middlesex and Union Counties to New York can be reassigned to feed riders to rail stations and serve suburb-suburb trips.

Conclusion

The Jersey Shore already features rail infrastructure and has the population density to support frequent, all-day transit service. Transit that serves a wide range of trips would significantly improve quality of life for a large portion of Monmouth County. The upgrades required to achieve that are well within reach and would cost a fraction of the expense of continuing to widen highways.

Photo Credits

Photo copyright KO Pix, used with permission under a Creative Commons License

Left photo copyright Corchis, used with permission under a Creative Commons License. Right photo copyright Ken (njt4148), used with permission under a Creative Commons License.

Photo copyright Pi.1415926535, used with permission under a Creative Commons License.

Left and right photos copyright GK tramrunner229, used with permission under a Creative Commons License.

All other photos copyright ETA members and used with permission.

Service map baselayers obtained by screen captures of Open Street Map content.