Getting the Most out of East Side Access

A Long Island Rail Road train at the new Grand Central Madison [1]

The purpose of all expanded infrastructure is improved service. With the opening of the East Side Access project imminent, the MTA has proposed a new Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) schedule to take advantage of this new infrastructure. This is the region’s chance to decide what future LIRR service should look like.

INTRODUCTION

The opening of the MTA's East Side Access program represents the culmination of over fifty-four years of transit planning in greater New York. For the first time, the trains of the Long Island Rail Road will run not only to their traditional terminal of Penn Station but to Grand Central Terminal, as well. This will not only increase the number of trains that can be run along what is already the nation's busiest commuter railroad, but will also give its riders direct access to both the East and West Sides of Manhattan, as well as a direct connection to its sibling service, Metro-North.

The inauguration of ESA represents a tremendous opportunity for the region to reimagine transportation on Long Island. However, while the proposed service plan for ESA does make some progress, it does not go as far as it should to ensure quality transit service for New York in a post-Covid age. The MTA’s current proposal reflects operating principles that are still rooted in the mid-twentieth-century North American paradigm of peak-oriented commuter rail, denying the region the full benefits of its massive new investment.

Instead, Long Island needs a service plan that better serves all types of riders—throughout the day and on weekends—by taking its inspiration from the practices of global peer cities. With a service network that is already largely electrified and fully outfitted with high-floor, level-boarding platforms, the LIRR already has most of the infrastructure it needs to provide truly world-class transit service. Home to eight million people, about 40% of the total population of New York State, and comprising around 2.5% of the state's land, Long Island, Brooklyn, and Queens are ideally suited to take advantage of better transit service.

Ultimately, with ESA, Long Island now has the opportunity to pave a new path and demonstrate a new paradigm for train service in the US: regional rail.

NETWORK DESIGN PRINCIPLES

The service on the LIRR network should appeal to as many people for as many different types of trips as possible. The offering needs to be predictable and easy to use. Trains must run frequently, defined here as headways no greater than 10 minutes wherever infrastructure allows, so that riders can just show up and go.

Resilience in the face of a changing world

Emerging ridership trends show that ridership has recovered best on off-peak trains. With the future of five-day-a-week-in-office work very much in doubt, it is crucial that the LIRR broaden its conception of the riders and trips it serves. To do otherwise would both perform a disservice to Long Island residents and imperil the organization’s own future. Moreover, the changes that the LIRR would have to make to its operating pattern would facilitate more straightforward crew scheduling. Today’s peak-heavy service requires many staff to work in the morning, rest during the midday, and come back on duty in the evening. This practice, known as a split shift, costs more per service hour than planning crews to work a continuous day. Added off-peak service would also amortize the capital costs of trains and infrastructure across more paying riders.

Show up and go with clockface scheduling

Trains should run frequently all day every day well into the night. Riders should be able to expect a train to arrive within minimal wait time on the platform and not need to consult a schedule. In line with peer operations in the rest of the world, the LIRR’s off-peak frequency should never drop below half that of the peak, and ideally the same frequency should be maintained all day while varying train lengths as necessary.

Moreover, the trains should come at the same times after the hour at a consistent interval, which is a practice known as clockface scheduling. While the proposed plan makes progress in this area, several lines’ proposed schedules still contain alternating headways, for example 22 and 38 minutes after the hour. Many trains deviate from a true clockface schedule by a few minutes, forcing riders to check the timetables so they do not miss their train. Schedules should be modified to create clockface schedules, for example, at 22 and 52 minutes per hour, wherever possible.

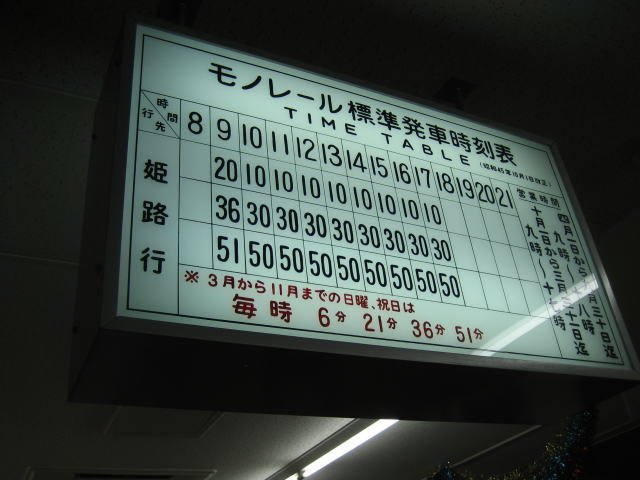

A clockface schedule from Japan showing consistent 20-minute frequency throughout the day [2]

Legible routes

Outside major hubs, lines should have as few stopping patterns as possible so that riders can reach intermediate stations as easily as the main ones. Riders walking up to intermediate stations should be able to grab the first train in the right direction without worrying where it will go. Local trains should make all the stops. Express trains, when they exist at all, should also not make varying stopping patterns.

Inbound trains from a single branch should always head to the same hub. The current service proposal would split trains on each branch between Grand Central and Penn Station, a practice often termed reverse branching. Dedicating each branch to a single hub not only reduces complexity for riders, but it also reduces the amount of merges at junctions, improving reliability.

Embracing transfers

It is infeasible to give everyone a one-seat ride to everywhere they may want to go. Historically, greater New York commuter rail service has tried to maximize one-seat rides and express service between Manhattan and outlying communities. However, this requires complex service patterns and inconveniences Queens and inner Nassau riders or those not traveling to or from the urban core. A few more one-seat rides were made possible at the cost of the great majority of possible trips.

Modern regional rail prioritizes all of the aforementioned principles and avails itself of modern trains’ aggressive acceleration and braking rates so that trains make as many stops as possible. Whether transfers are timed, such that trains from different branches arrive simultaneously or nearly so, or untimed, such that trains are uncorrelated but frequent, riders can always transfer with minimal added wait time, no matter when they arrive at the station.

SERVICE AND OPERATIONS ANALYSIS

Splitting service between Penn Station and Grand Central

The current ESA service plan would split service on most branches with service to Manhattan between Penn Station and Grand Central. Moreover, branches have uneven service to each terminal; schedules typically contain long gaps in service of 30-50 minutes followed by multiple trains every 3-5 minutes. This service arrangement confuses potential riders. Going forward, the LIRR should prioritize legibility. All trains on a given branch should serve only one terminal.

Moreover, the LIRR should revisit the proposed overnight gaps in Grand Central service. People still need transit service at those hours, yet the proposed schedule contains a 3 hour 56 minute gap in service to Grand Central between 1:52 AM and 5:48 AM, and a 4-hour gap in trains leaving Grand Central between 1:45 AM and 5:45 AM. This mirrors the closure of Metro-North’s Grand Central Terminal. Penn Central implemented that closure in 1973 to drive homeless people out of the station, and it received criticism at the time. Public space closures impose significant inconvenience while failing to address the root cause of homelessness. Schedules should serve riders over as much of the day as possible with minor downtime only to allow for maintenance.

Off-peak/weekend service

In the proposed timetable, only the Huntington, Ronkonkoma, and West Hempstead Branches receive increased off-peak and weekend service. By contrast, service would still run hourly on weekends and off-peak on the West Hempstead, Far Rockaway, Long Beach, and Hempstead Branches.

Services should run at least every 30 minutes all day, seven days a week on all of these branches’ electrified portions. Wherever infrastructure allows, services should run at least every 15 if not 10 minutes all day to allow untimed transfers at branch points.

Huntington and Ronkonkoma Branches

Following major infrastructure upgrades on the Main Line, the East Side Access service plan would fill large gaps in reverse-peak service on the Ronkonkoma and Huntington Branches. This is great progress, but more should be done.

Ronkonkoma Branch service would double to run every 30 minutes during the day and on weekends. Huntington Branch service would also increase to every 30 minutes during the day. All Ronkonkoma trains would stop at Hicksville and Mineola. Huntington trains would make all stops to New Hyde Park, and every other weekday Huntington train would stop at Floral Park, supplementing Hempstead Branch service and improving connections to Bellerose, Queens Village, and Hollis.

Main Line local stops would see major service improvements. All trains outside rush hours would make all of these stops. Weekend service would double to every 30 minutes. Particularly onerous service gaps at New Hyde Park and Carle Place on the Main Line would be filled in. All electric trains would start or end at Huntington. Nearly all Huntington Branch trains would stop at Hicksville, and fewer trains would skip Mineola and Main Line local stops.

Still, the proposed service would leave large service gaps that should be closed. Major transfer stations and Main Line local stops would still see multi-hour gaps in at least one direction during weekdays, which are fillable by changing split shifts amongst train crew to continuous ones. These gaps should be filled with trains every 10 minutes to both Huntington and Ronkonkoma, making intra-Long Island trips within electric territory feasible at any time of day.

Hempstead Branch

Densely populated by Nassau County standards, the communities along the Hempstead Branch would benefit from frequent all-day service. The branch’s single-track section just north of its terminus is short enough to allow a 10-minute service interval, thus boosting frequency along the Main Line west of Floral Park and enabling all Ronkonkoma and Huntington services to run express west of Floral Park.

Babylon, Long Beach, and Far Rockaway Branches

The proposal still contains unnecessarily complex South Shore service patterns. Many Babylon Branch trains and some Long Beach Branch trains would skip Lynbrook, and some Far Rockaway Branch trains would skip Valley Stream, reducing the offering’s usability, particularly for suburb-to-suburb rides. For example, riders seeking to travel from Locust Manor to Lindenhurst between 6 PM and 9 PM have only six trip options, five of which require backtracking to Jamaica, taking 62 to 81 minutes, and one of which requires taking four trains.

Adding stops at Lynbrook or Valley Stream to trains that are currently planned to skip these stations would nearly double the possibilities for travel between those two stations during that window, and substantially shorten travel times to between 47 and 56 minutes. These added stops would cost each of these trains at most 2 minutes of end-to-end travel time each, which can likely be recouped through more aggressive acceleration and braking and raising of speed limits on curves to the maximum allowable by track geometry.

Currently, Long Beach trains would run to Penn Station weekdays during the off-peak, but to Grand Central weekends, while Far Rockaway Branch trains do the reverse. Instead, all trains on each branch should run only to one terminal. Moreover, the LIRR should seek to close gaps in service that the proposal would leave in place, such as that from Long Beach between 12:01 AM and 4:15 AM.

Overall, each of these three branches can support 10-minute all day service making all stops without reverse-branching to Grand Central Madison and Penn. As is the case across electric territory wherever double-track exists, short intervals enable untimed transfers at branch points and thus everywhere-to-everywhere trips.

West Hempstead Branch

Under the proposed schedule, service on the West Hempstead Branch would see major improvements. Trains would now run hourly during the off-peak and weekends and would continue to Atlantic Terminal. Limited peak service would connect to Penn Station and Grand Central. All West Hempstead trains would now stop at St. Albans, which would now receive hourly midday service. However, efforts should be made to deliver twice-hourly service. As the current proposal would decrease the number of Babylon Branch trains calling there, restoring the St. Albans stops on these runs would close much of this gap.

Disappointingly, the proposed schedule has no trains leaving West Hempstead between 11:57 PM and 5:22 AM or arriving there between 12:30 AM and 7:07 AM. There would be a 105-minute gap in reverse-peak service at Locust Manor, Laurelton, and Rosedale, between 5:06 AM and 6:51 AM.

Furthermore, the LIRR should continue adding frequency to the South Shore branches to the point where untimed transfers at Valley Stream are possible all day. These lines serve some of the most densely populated communities of Nassau County. Running the Far Rockaway, Long Beach, and Babylon Branches at 10-minute intervals all day would enable the West Hempstead Branch to run as a bi-hourly shuttle to Valley Stream where riders could make effectively untimed transfers both inbound towards Manhattan and outbound. West Hempstead ridership can be expected to improve more dramatically than on other electric branches given it is the electrified branch with the sparsest service provision at present and serves a relatively densely populated corridor close to Manhattan.

Brooklyn service

While the proposal contains some notable improvements for Brooklyn service, its worst shortcomings lie here too. On a positive note, all trains would stop at Nostrand Avenue and East New York. However, the elimination of most through service to Brooklyn, in combination with infrequent shuttle service (every 12 minutes peaks and 20 minutes off-peaks) would yield a net decrease of six trains per peak period. The plan would significantly increase mean travel times for Brooklyn riders. Travel times in the peaks would increase by an average of 11-12 minutes. Worse, during off-peak hours, many trips to or from points outside of Jamaica would require transfers of 20 minutes or more.

Going forward, service should be increased to every 7.5 minutes during the peak, and at least every 15 minutes off-peak, as was proposed in 2010. The LIRR has stated that it currently cannot provide this much service due to a shortage of equipment. Planners should consider, at least for the near term, reassigning equipment from other branches by reducing turnaround times, eliminating midday layovers, and running shorter trains more frequently. Of note, just prior to the pandemic, the average morning peak LIRR train was loaded under its seated capacity at Penn Station.

Port Washington Branch

Service on the Port Washington Branch would improve significantly under the proposed schedule. Off-peak and weekends, all Port Washington trains would make all stops. Midday service on the Port Washington Branch would no longer feature complicated skip-stop patterns. All Queens stations would receive at least hourly midday service. Fewer reverse peak trains would skip stops, and major gaps in service at Plandome and Murray Hill would be closed.

However, frequencies still leave much to be desired considering the population density of northeast Queens and northwest Nassau County west of Great Neck where double-track presently ends. With a timed overtake of locals by expresses at Willets Point, both locals and expresses can operate on 10-minute intervals each west of Great Neck.

Long Island City

Despite major population growth and an influx of new development in the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens, the proposed schedule would still include no off-peak or weekend service to Hunterspoint Avenue or Long Island City Stations. These stations should receive service seven days per week all day, ideally via a reactivated Lower Montauk line in order to maintain 48 train paths hourly each way serving Midtown.

Queens service

The planned Queens service would not be adequate for the borough’s needs. Generally, the proposed schedule offers trains every 30 minutes on the Port Washington Branch and every 60 minutes to stations in Southeast Queens. Midday and weekend service at Forest Hills and Kew Gardens would run every 30 minutes and every 60 minutes to Penn Station or Grand Central. The combination of low frequency and the fare premium over the parallel subway means that few people would use either commuter rail station. Moreover, most trains would stop at only one of Woodside, Forest Hills, or Kew Gardens, rendering travel between these stations impractical.

Instead, the LIRR should have all trains running via the Main Line local tracks stop at all three stations between Jamaica and Penn Station. This change would increase capacity, enable increases in reverse-peak service, and reduce schedule complexity. Perhaps unexpectedly, this move would consolidate all Main Line local service onto fewer trains, which would enable more trains to run express off-peak.

The proposed weekend service at Hollis, Queens Village, Locust Manor, Laurelton, and Rosedale is actually better on weekends than weekdays, with service every 30 minutes on weekends and every hour on weekdays. St. Albans would see hourly service during both time frames.

Going forward, the density of central Queens warrants service every 5 to 10 minutes at all times. Such frequent service on all lines serving Jamaica would enable untimed transfers there connecting Queens to many points on Long Island.

Kew Gardens only sees hourly service today, limiting the usefulness of LIRR for Queens residents [3]

Diesel service

Timing appropriate eastbound electric runs to connect with less-frequent diesel service is acceptable in the near term given both current and expected ridership patterns in diesel territory lend themselves to intercity-type mainline rail more than urban or suburban mainline rail. Running electric trains at headways no greater than 10 minutes or six trains hourly spaced evenly will enable untimed transfers westbound from diesel runs at the ends of electrified trackage.

Other than some adjustments to even out headways, the current service plan contains few changes for diesel lines. It would add no service to Hunterspoint Avenue and only one more PM train from Penn Station to Speonk; multi-hour gaps in service would remain. While there are obstacles to running service as frequently as that closer to Manhattan, including long stretches of single-track, and short platforms, the infrastructure can already support large increases over today’s offering.

None of the above should preclude any extension of electrification into present-day diesel territory. While electrification and re-signalling of diesel branches are outside the scope of this statement, systemic capital investment should be encouraged in the interest of providing reliable and frequent through service from the termini of the longest branches to the urban core. Such extensions will speed Eastern Long Island transit and decarbonize disproportionately long trips.

PHASING AND FUTUREPROOFING

Infrastructure constraints

The recommendations above do not require any major capital improvements other than those already under way or approved under the 2019-2024 Capital Plan. However, future capital planning should take into account potential changes in ridership patterns in response to a frequent all-day timetable and opportunities to shape ridership in ways conducive to fiscal, socioeconomic, and environmental goals. For example, if the increase in fare revenue from increasing West Hempstead Branch service to every 30 minutes all day exceeds the marginal operating cost of such service, double track and longer platforms for that branch are worth consideration.

Equipment requirements

Running 10-minute all day headways on all electrified branches except where constrained by long single-track segments is feasible with the existing fleet of M7 and M9 electric multiple units, and additional M9 orders and options on the books will enable replacement of all diesel services given full electrification of diesel branches. Future orders for rolling stock should prioritize high acceleration and fast passenger entry and egress such that stop penalties and dwell times at stations can be minimized, thus enabling trip times on future local services to match those on present-day express services.

Bus and subway integration

While improving integration of LIRR with subway and bus services is outside the scope of this stat, future LIRR service plans should be coordinated with subway and bus service planning. Improving ease of transfers to bus and subway lines, ideally with integrated fares, can boost LIRR ridership beyond what can be achieved by implementing consistent all-day frequent mainline rail service alone.

Through-running scenarios

Atlantic Branch to Jersey City and beyond

Conversion of the Atlantic Branch from a branch to a trunk would add capacity for 12 potential hourly runs east of Valley Stream. This step is necessary for through service from West Hempstead or Garden City to the urban core, since 10-minute headways on all other electrified branches east of Jamaica plus 5-minute headways on the Port Washington Line would require use of all train paths to Penn and Grand Central Madison.

Construction cost reform would enable consideration of through-running the Atlantic Branch to a new line across Lower Manhattan via the Bergen Arches to Northern New Jersey. This project would add around another 12 hourly runs. Assuming ridership responds favorably to 10-minute headways to Far Rockaway and Long Beach, halving headways on either or both to 5 minutes is justifiable based on population density in southwest Nassau County and southeast Queens.

Lower Montauk Line to Union City and beyond

Presently unelectrified and lightly used for freight and non-revenue equipment movements, the Lower Montauk Branch passes a chain of neighborhoods beyond a half-mile walk to the nearest subway or active mainline rail stop. While its use as a standalone rapid transit line is justifiable for that reason, its broader utility lies in enabling additional shortening of headways east of Jamaica to as low as five minutes, including the West Hempstead and Babylon branches and, if electrified to the terminus, the Oyster Bay branch. Furthermore, construction cost reform would enable consideration of a westward extension across Manhattan into New Jersey to connect with the West Shore Line and possibly the Erie Main Line, either of which would serve communities currently without any rail service.

CONCLUSION

While the LIRR’s proposed East Side Access schedule makes some progress toward standardizing service, much more extensive service improvements are possible with minimal capital investment. Planners should treat the recommendations here as the first phase of implementing practices for modern, competitive regional rail that not only positions LIRR on a sounder fiscal footing but also more broadly encourages communities across Long Island to embrace the LIRR as an integral part of their lives, versus a small boost to an otherwise car-centric way of life. This spreads the benefits of the LIRR across the socio-economic spectrum and makes Long Island more environmentally resilient well into this century.

Footnotes

Photo copyright Marc A. Hermann / MTA, used with permission.

Photo copyright Terumasa, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo copyright Shaul Picker, via Wikimedia Commons.